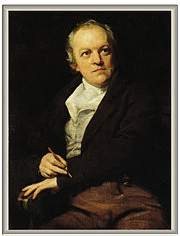

Chapter I. - Introducing William Blake

William

Blake (1757-1827), who lived in the latter half of the

eighteenth century and the early part of the nineteenth, was a

profoundly stirring poet who was, in large part, responsible for

bringing about the Romantic movement in poetry. He was able to

achieve "remarkable results with the simplest means";

and was one of several poets of the time who restored "rich

musicality to the language" (»1).

His research and introspection into the human mind and soul has

resulted in his being called the "Columbus of the psyche,"

and because no language existed at the time to describe what he

discovered on his voyages, he created his own mythology to describe

what he found there (»2).

He was an accomplished poet, painter, and engraver. |

|

Despite

the work of such 17th century baroque poets as Henry Vaughan (1622-1695), and Richard Crashaw (1612-1649), England

had no visionary tradition in its literature before the brilliant English

poet, painter, engraver and visionary mystic - William Blake. His hand-illustrated

series of lyrical and epic poems, beginning with Songs

of Innocence (1789) and Songs

of Experience (1794), form one of the most strikingly original

and independent bodies of work in the Western cultural tradition. Blake

is now regarded as one of the earliest and greatest figures of Romanticism.

Yet he was ignored by the public of his day and was called mad because

he was single-minded and unworldly; he lived on the edge of poverty

and died in neglect.

"I

know I am inspired!" could be the foundation of his obscurity as

well as of his dynamic enthusiasm. He was ambitious for fame; he longed

for, even demanded, an audience as enthusiastic as himself, to build

the Jerusalem he was looking for in England's green and pleasant land.

He was after all writing at a time when the Age of reason was turning

into an Age of Enthusiasm (»3).

But he had a naive, almost arrogant confidence in the power of his own

inspiration. Burning with its fire, convinced that to hear him must

be to applaud, he failed to realize that he must also address himself

to the minds of his audience before they could hear him. He never made

any concessions to them, and as a result they made none to him. He sought

to project his inner enthusiasm on to the public, but chose one method

after another that ensured that his audience would regard his enthusiasms,

not as inspiration, but as mere eccentricity or worse.

Blake

scholars disagree on whether or not Blake was a mystic. In the Norton

Anthology, he is described as "an acknowledged mystic, [who]

saw visions from the age of four" (»4).

Frye, however, who seems to be one of the most influential Blake scholars,

disagrees, saying that Blake was a visionary rather than a mystic. "'Mysticism'

. . . means a certain kind of religious techniques difficult to reconcile

with anyone's poetry," says Frye (»5).

He next says that "visionary" is "a word that Blake uses,

and uses constantly" and cites the example of Plotinus, the mystic,

who experienced a "direct apprehension of God" four times

in his life, and then only with "great effort and relentless discipline."

He finally cites Blake's poem "I rose up at the dawn of day," in which Blake states,

"I

am in God's presence night & day,

And he never turns his face away."

Besides

all of these achievements, Blake was a social critic of his own time

and considered himself a prophet of times to come. Frye says that "all

his poetry was written as though it were about to have the immediate

social impact of a new play" (»6).

His social criticism is not only representative of his own country and

era, but strikes profound chords in our own time as well. As Appelbaum

said in the introduction to his anthology English Romantic Poetry,

"[Blake] was not fully rediscovered and rehabilitated until a full

century after his death". For Blake was not truly appreciated during

his life, except by small cliques of individuals, and was not well-known

during the rest of the nineteenth century (»7).

Blake's life might

seem uneventful, but his inner life was so exciting that it did not

matter. His enthusiasm lifted him out of London into Jerusalem - or

rather, brought Jerusalem into London and turned a rainbow over Hyde

Park into a gateway to heaven. Blake's enthusiasm are not the toad-like

crazes of a perpetually unsatisfied man, but the developing insights

of someone with a wide-ranging mind responding to life's rejections

of his hopes, not by losing hope, but by rebuilding it. And each stage

has its own artistic correlative.

Blake

was born November 28, 1757, in London. His father was a hosier living

in Broad Street in the Soho district of London, where Blake lived most

of his life. He was the second son of a family of four boys and one

girl. Only his younger brother Robert was of great significance in William's

life, as he was the one to share his devotion to the arts (»8).

William grew up in London and later described the visionary experiences

he had as a child in the surrounding countryside, when he saw angels

in a tree at Peckham Rye and the prophet Ezekiel in a field. William

very soon declared his intention of becoming an artist in 1767, and

was allowed to leave ordinary school at the age of ten to join a drawing

school and started to attend the drawing school of Henry Pars in the

Strand. He educated himself by wide reading and the study of engravings

from paintings by the great Renaissance masters. Here he worked for

five years, but, when the time came for an apprenticeship, his father

was unable to afford the expense of his entrance to a painter's studio.

A premium of fifty guineas, however, enabled him, aged nearly fifteen,

to enter on 4 August 1772 the workshop of a master-engraver, James

Basire. There, in Great Queen Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields,

he worked faithfully for seven years, learning all the techniques of

engraving, etching, stippling and copying. This thorough training equipped

him as a man who could later claim with justice that he was one of the

finest craftsmen of his time, one moreover able not only to develop

and improve the conventional modes throughout his life, but also to

invent methods of his own. Basire sent him to make drawings of the sculptures

in Westminster Abbey, and thus awakened his interest in Gothic art (»9).

On

completion of his apprenticeship in 1779 Blake entered the Royal Academy

as an engraving student. His period of study there seems to have been

stormy. He took a violent dislike to Sir Joshua Reynolds, then president

of the Royal Academy, rebelling against his aesthetic doctrines, and

felt that his talents were being wasted. He was initially influenced

by the engravings he studied of the works of Michelangelo and Raphael. He made drawings from the antique in the

conventional manner and some life studies, though he soon rejected this

form of training, saying that 'copying nature' deadened the force of

his imagination. For the rest of his life he exalted imaginative art

above all other forms of artistic creation, scarcely any of his productions

being strictly representational.

While

still at the Academy he was earning his living by engraving for publishers

and was also producing independent watercolours. At this time his friends

included the "roman group" of brilliant young artists, among

them the sculptor John Flaxman and the painter Thomas

Stothard (»10).

He also came into contact with the highly original Romantic painter Henry Fuseli at this time, whose work may have influenced

him. He began his career as an engraver and artist, and was an apprentice

to Henry Fuseli for a time. He then became deeply impressed with the

work of his contemporary figurative painters like James Barry, John

Mortimer, and Henry Fuseli, who, like Blake, depicted dramatically posed

nude figures with strongly rhythmic, linear contours. Fuseli's extravagant

pictorial fantasies in particular freed Blake to distort his figures

to express his inner vision (»11).

In 1784 he set up a print shop; although it failed after a few years,

for the rest of his life Blake eked out a living as an engraver and

illustrator (»12).

In

the late 1760s and '70s the "roman group" circle of British

painters in Rome had already begun to find academic precepts inadequate.

James Barry, the brothers John and Alexander Runciman, John Brown, George

Romney, and the Swiss-born Henry Fuseli favoured themes – whether

literary, historical, or purely imaginary – determined by a taste

for the pathetic, bizarre, and extravagantly heroic. Mutually influential

and highly eclectic, they combined, especially in their drawings, the

linear tensions of Italian Mannerism with bold contrasts of light and

shade. Though never in Rome, John Hamilton Mortimer had much in common

with this group, for all were participants in a move to found a national

school of narrative painting. Fuseli's affiliations with the German

Romantic Sturm und Drang writers predisposed him, like Flaxman,

toward the "primitive" heroic stories of Homer and Dante.

Flaxman himself, in the two-dimensional linear abstraction of his drawings,

a two-dimensionality implying rejection of Renaissance perspective and

seen for instance in the expressive purity of "Penelope's Dream"

(1792-93), had important repercussions throughout Europe. Both Fuseli

and Flaxman highly influenced both Blake's interest in mythology and

the heroic and also his attitude towards art (»13).

|

William

Blake absorbed and outstripped the Fuseli circle, evolving new

images for a unique private cosmology, rejecting oils in favour

of tempera and watercolour, and depicting, as in "Pity"

(1795), a shadowless world of soaring, supernatural beings. His

passionate rejection of rationalism and materialism, his scorn

for both Sir Joshua Reynolds and the Dutch Naturalists, stemmed

from a conviction that "poetic genius" could alone perceive

the infinite, so essential to the artist since "painting,

as well as poetry and music, exists and exults in immortal thoughts."

(»14) |

In

his painting (as well as in his poetry), Blake seemed to most of his

contemporaries to be completely out of the artistic mainstream of their

time. His art was in fact far too adventurous and unconventional to

be easily accepted in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

He has been called a pre-romantic because it was not only in poetry

that he rejected neoclassical literary style and modes of thought, his

graphic art too defied 18th-century conventions. Always stressing imagination

over reason, he felt that ideal forms should be constructed not from

observations of nature but from inner visions. His rhythmically patterned

linear style is also a repudiation of the painterly academic style.

Blake's attenuated, fantastic figures go back, instead, to the medieval

tomb statuary he copied as an apprentice and to Mannerist sources. The

influence of Michelangelo is especially evident in

the radical foreshortening and exaggerated muscular form in one of his

best-known illustrations, popularly known as The

Ancient of Days, the frontispiece to his poem Europe,

a Prophecy (1794). (»15)

For

this reason Blake remained virtually unknown until Alexander Gilchrist's

biography was published in 1863, and he was not fully accepted until

his remarkable modernity and his imaginative force, both as poet and

artist, were recognized in the twentieth century (»16).

In spite of this his paintings belong to a recognizable artistic tradition,

that of English figurative painting of the later 18th century.

Throughout

his life Blake stressed the superiority of line, or drawing, over colour,

commending the "hard wirey line of rectitude." He condemned

everything that he felt made painting indefinite in contour, such as

painterly brushwork and shadowing. Finally, Blake stressed the primacy

of art created from the imagination over that drawn from the observation

of nature. The figures in Blake's many prints and watercolour and tempera

paintings are notable for the rhythmic vitality of their undulating

contours, the monumental simplicity of their stylised forms, and the

dramatic effectiveness and originality of their gestures. He also showed

himself a daring and unusually subtle colourist in many of his works.

Much of Blake's painting was on religious subjects: illustrations of

the work of John Milton, his favourite poet (although

he rejected Milton's Puritanism), for John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, and for the Bible, including 21 illustrations

to the 'Book of Job'. Blake's favourite subjects were episodes

from the Bible, along with episodes found in the works of Milton and

Dante. Among his secular illustrations were those for an edition of Thomas Gray's poems and the 537 watercolours for Edward

Young's Night Thoughts - only 43 of which were published.

His illustrations for the Book of Job were done late in life, and they

mark the summit of his achievement in the visual arts (»17).

The

spiritual, symbolical expression of Blake's complex sympathies, his

ability to recognize God in a single blade of grass, inspired Samuel

Palmer, who, with his friend Edward Calvert, extracted from nature a

visionary world of exquisite, though short-lived, intensity (»18).

On

August 18, 1782, Blake married a poor, illiterate girl, Catherine

Boucher, who was to make a perfect companion for him.

Having married, Blake left his father's home and rented a small house

round the corner in Poland Street, being joined there by his brother

Robert after their father's death in 1784. William then began to train

Robert as an artist. Meanwhile he himself, self-educated, had already

acquired a wide knowledge of poetry, philosophy and general literature,

and was ready to take his place among people of intelligence. He attended

social gatherings of intellectuals, to whom he even communicated his

own poems, sometimes singing them to tunes of his own composition (»19).

Flaxman introduced him to the Rev. Anthony S. Mathew and his wife, and for a time Blake was one of the chief attractions

at their literary parties. Flaxman and Mathew paid for the printing

of a collection of verses by their young friend, Poetical

Sketches (1783). A preface provides the information that

the verses were written between Blake's 12th and 20th years. This is

a remarkable first volume of poetry, and some of the poems contained

in it have a freshness, a purity of vision, and a lyric intensity unequaled

in English poetry since the 17th century (»20).

Blake's

visits to the Mathews' eventually became less frequent and finally ceased.

Nevertheless, in the 1780s he was one of a group of progressive-minded

people that met at the house of Blake's employer, the Radical bookseller Joseph Johnson. His mind was developing an unconventional

and rebellious quality, acutely conscious of any falsity and pomposity

in others, so that about 1784 or 1787 he wrote a burlesque novel, known

as An Island in the Moon, in which he ridiculed contemporary manners

and conventions, and in which members of this group are satirized.

In

1784, after his father's death, Blake started a print shop in London

and took his younger brother Robert to live with him as assistant and

pupil. Early in 1787 Robert fell ill and in February he died; and William,

who had nursed him devotedly, later said that he had seen Robert's soul

joyfully rising through the ceiling. At the moment of Robert's death

his visionary faculty enable him to see "the released spirit ascend

heavenwards, clapping its hands for joy" (»21).

For the rest of his life William claimed that he could communicate with

this brother's spirit and gain strength from his advice. He also said

that Robert had appeared to him in a vision and revealed a method of

engraving the text and illustrations of his books without having recourse

to a printer.

This method was Blake's

invention of what he called "illuminated printing," in which,

by a special technique of relief etching, each page of the book was

printed in monochrome from an engraved plate containing both text

and illustration: an invention foreshadowed by his friend, George

Cumberland. Although his method of illuminated printing is not completely

understood, the most likely explanation is that he wrote the words

– not in reversed script, as an engraver must normally do –

and drew the pictures for each poem on a copper plate, using some

liquid impervious to acid, which when applied left text and illustration

in relief. After etching away the unwanted material, the plate became

one large piece of type, to be inked and printed on his engraver's

press. Ink or a colour wash was then applied, and the printed picture

was finished by hand in watercolours. Thus each print is itself a

unique work of art. As an artist Blake broke the ground that would

later be cultivated by the Pre-Raphaelites.

Most

of Blake's works after the Poetical Sketches were engraved

and "published" in this way, and so reached only a limited

public during his lifetime. Today these "illuminated books,"

with their dynamic designs and glowing colours, are among the world's

art treasures. Most of Blake's paintings (such as "The Ancient

of Days" or the frontispiece to Europe:

a Prophecy) are actually prints too made from copper plates,

which he etched in his 'illuminated printing' method.

The

product of his first enthusiasm is the foundation of all the rest; it

reveals him, not as the preacher of doctrines of free innocence, or

as a mystical thinker, but as that typical eighteen-century figure,

the inventor. In other hands his invention might well have succeeded:

the re-creation in modern guise of the medieval illuminated book, text

and design together as unity, but using new techniques to make reproduction

feasible. Illustrated books were much in demand, but not easy to produce.

Blake was writing poetry; how better to see it published than in the

style of medieval illuminated book, a hand-made, unique work of art?

As a poet and artist, he could create the whole work, and the result

would be as fine as an illustrated manuscript. But there was no need

for the work to remain unique; as an engraver he had the skill and the

means to make multiple copies. Many of the plates, especially in the Songs, America and Europe, fulfil his hopes and

make one artistic unity, poem and design (»22).

In

his readiness to invent new techniques, Blake was typical of his age.

His "illuminated books" were usually coloured with watercolour

or printed in colour by Blake and his wife, bound together in paper

covers, and sold for prices ranging from a few shillings to 10 guineas.

He must have thought his fortune was made. True, it was a clumsy process

by our standards, and did not produce a very well-defined or legible

text, but it satisfied Blake's needs, and he used it as long as he wrote

poetry. It might well have made him a success, if he had produced works

that the public wanted to see. But apart from Songs

of Innocence, a children's poetry book which might well

have found a market, he used it almost entirely for his own ideological

campaign. Even this might have succeeded – Shelley found an audience

– but Blake's books used an idiom that even his friends found

hard to understand.

William

Blake created a unique form of illustrated verse; his poetry, inspired

by mystical vision, belongs to the most original lyric and prophetic

poetry in the language. His poetry and visual art are inextricably linked,

therefore to fully appreciate one you must see it in context with the

other. As was to be Blake's custom, he illustrated the Songs with designs that demand an imaginative reading of the complicated dialogue

between word and picture (»23).

You could say, he was one of those 19th century figures who could have

and should have been "beatniks", along with Rimbaud, Verlaine, Manet, Cézanne and Whitman.

The

first books in which Blake made use of his new printing method were

two little tracts, There is No Natural Religion and All Religions are One,

engraved about 1788. They contain the seeds of practically all the subsequent

development of his thought. In them he boldly challenges accepted contemporary

theories of the human mind derived from Locke and the prevailing rationalistic-materialistic

philosophy and proclaims the superiority of the imagination over other

"organs of perception," since it is the means of perceiving

"the Infinite," or God. Immediately following these tracts

came Blake's first masterpieces, in an astonishing outburst of creative

activity: Songs of Innocence and The Book of Thel (both engraved

1789), The French Revolution (1791), The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Visions of the Daughters of Albion (both engraved 1793), and Songs of Innocence

and Experience (1794). The production of these works coincided

with the outbreak of the French Revolution, of which Blake, like the

other members of the group that met at Johnson's shop, was at first

an enthusiastic supporter. Blake significantly differed from other English

revolutionaries, however, in his hatred of deism, atheism, and materialism,

and his profound, though undogmatic, religious sense (»24).

Blake

did, however, approve of some of the measures that individuals and societies

took to gain and maintain individual freedom. As Appelbaum said, "He

was liberal in politics, sensitive to the oppressive government measures

of his day, [and] favorably inspired by the American Revolutionary War

and the French Revolution" (»25).

This is the time when Blake keeps an intensive communication with the

revolutionary American political thinker Thomas Paine.

According to Keynes, Blake wrote many positive and appreciative things

about him, for instance, such as "The Bishop never saw the Everlasting

Gospel any more than Tom Paine" (»26).

As "London" shows, however,

Blake did not entirely approve of the measures taken to forward the

causes he longed to advance: "London" refers to how the "hapless

Soldier's sigh/ runs in blood down Palace walls" ["London"

791]. Among many other events which took place during the French Revolution,

this could possibly refer to the storming of the Bastille or the executions

of the French nobility.

Blake began writing

poetry at the age of 12, and his first printed work, Poetical

Sketches (1783), is a collection of youthful verse. Amid

its traditional, derivative elements are hints of his later innovative

style and themes. As with all his poetry, this volume reached few

contemporary readers. Blake's most popular poems have always been Songs of Innocence (1789).

These lyrics are notable for their eloquence. In 1794, disillusioned

with the possibility of human perfection, Blake issued Songs of Experience,

employing the same lyric style and much of the same subject matter

as in Songs of Innocence. Both series of poems take on deeper resonances

when read in conjunction. Innocence and Experience, “the two

contrary states of the human soul,” are contrasted in such companion

pieces as "The Lamb" and "The Tyger". Blake's

subsequent poetry develops the implication that true innocence is

impossible without experience, transformed by the creative force of

the human imagination.

Songs of Innocence is Blake's first masterpiece of "illuminated printing."

Blake made the twenty-seven plates of Songs of Innocence, dating the

title page 1789, and thus initiated the series of his now famous Illuminated

Books. The impulse to produce his poems in this form was partly due

to his cast of mind, whereby the life of the imagination was more

real to him than the material world. This philosophy demanded the

identification of ideas with symbols which could be translated into

visual images – word and symbol each reinforcing the other.

His lyrical poems have content enough to make them acceptable without

the visual addition, but he did not choose that they should be read

in this plain shape, and consequently his output of books reckoned

in numbers of copies was always very limited.

Songs of Innocence differs radically from the rather derivative

pastoral mode of the Poetical Sketches. In the Songs,

Blake took as his models the popular street ballads and rhymes for children

of his own time, transmuting these forms by his genius into some of

the purest lyric poetry in the English language. There is no reason

for thinking that when he composed the Songs of Innocence he

had already envisaged a second set of antithetical poems embodying Experience.

The Innocence poems were the products of a mind in a state of innocence

and of an imagination unspoiled be stains of worldliness. Public events

and private emotions soon converted Innocence into Experience, producing

Blake's preoccupation with the problem of Good and Evil. This, with

his feelings of indignation and pity for the sufferings of mankind as

he saw them in the streets of London, resulted in his composing the

second set. So in 1794 he finished a slightly rearranged version of Songs of Innocence with the addition of Songs

of Experience; the double collection, in Blake's own words

in the subtitle, "shewing the two contrary states of the human

soul." The "two contrary states" are innocence, when

the child's imagination has simply the function of completing its own

growth; and experience, when it is faced with the world of law, morality,

and repression. Songs of Experience provides a kind of ironic

answer to Songs of Innocence. The earlier collection's celebration

of a beneficent God is countered by the image of him in Experience,

in which he becomes the tyrannous God of repression. The key symbol

of Innocence is the Lamb, the corresponding image in Experience is the

Tyger (»27).

The

Tyger in this poem is the incarnation of energy, strength, lust, and

cruelty, and the tragic dilemma of mankind is poignantly summarized

in the final question, "Did he who made the Lamb make thee?"

Blake also viewed the larger society, in the form of contemporary London,

with agonized doubt in Experience, in contrast to his happy visions

of the city in Innocence. In the great poem "London",

which has been described as summing up many implications of Songs of

Experience, Blake describes the woes that the Industrial Revolution

and the breaking of the common man's ties to the land have brought upon

him. "London" is an especially powerful indictment of the

new "acquisitive society" then coming into being, and the

poem's naked simplicity of language is the perfect medium for conveying

Blake's anguished vision of a society dominated by money (»28).

When

Blake's first great enthusiasm gripped him, the world was in the ferment

of revolution. But Blake was convinced that art, the works of the imagination,

not political revolution, were the key to its renovation. In the first

group of legends (1789-93), Blake presents his case: the indestructibility

of innocence. The soul that freely follows its imaginative instincts

will be innocent and virtuous; nature protects this innocence and the

only sin is to allow one's nature to be prevented by law and custom.

Free love is only true love; law destroys both love and freedom (»29).

Some

see him as true nonconformist radical who numbered among his associates

such English freethinkers as Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft (»30).

But for Blake freedom could not come about except through the imagination.

The Bible presented a view, not of freedom, love, innocent happiness

and above all, imagination, but law. The world's images were all wrong.

Blake would put it right with a series of narrative poems in the new

medium, to illustrate the nature of imaginative truth. Poems such as 'The French Revolution' (1791), 'America', a 'Prophecy' (1793), 'Visions of the Daughters of Albion' (1793), and 'Europe, a Prophecy' (1794) express his condemnation of 18th-century political and social

tyranny. Political revolution was not in itself the antidote to tyranny,

but a symptom of mankind's awakening to the freedom of the spirit. In

the exercise of the imagination, the purity and inviolability of innocence

would reveal itself. The need for law, and tyranny itself, would not

wither at the hand of war, but at the breath of the free imagination.

Theological

tyranny is one subject of The Book of Urizen (1794), and the dreadful cycle set up by the mutual exploitation of

the sexes is vividly described in "The Mental Traveller" (circa 1803). (»31)

These books, including the Songs of Experience (1794), are devoted to discovering what had gone wrong.

Typically Blake did not reject his beliefs, but went on to improve them.

Now he understood that it was too simple to see the world's problems

as the hostility of evil minds against good - the tyrant threatening

the innocent imagination. His new visions emerged in his enthusiasm

for the plan of a great epic, Vala, which he started writing on the

black proofs of his Night Thoughts designs (»32).

Among the Prophetic Books is a prose work, The

Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790-93), which develops Blake's

idea that “without Contraries is no progression.” It includes

the "Proverbs of Hell", such as “The tygers

of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction”.

Blake

was experimenting in narrative as well as lyrical poetry at this time. 'Tiriel', a first attempt, was never engraved. The

Book of Thel, with its lovely flowing designs, is an idyll

akin to Songs of Innocence in its flowerlike delicacy and transparency.

In Tiriel and The Book of Thel Blake uses for the first time the long

unrhymed line of 14 syllables, which was to become the staple metre

of his narrative poetry (»33).

The fragment called 'The French Revolution' is a heroic attempt

to make epic poetry out of contemporary history.

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell satire, prophecy, humour, poetry, and philosophy are mingled in a way

that has few parallels. Written mainly in terse, sinewy prose, it may

be described as a satire on institutional religion and conventional

morality. In it Blake defines the ideal use of sensuality: "If

the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man

as it is, infinite." Blake reverses the tenets of conventional

Christianity, equating the good with reason and repression and regarding

evil as the natural expression of a fundamental psychic energy (»34).

As Appelbaum said of Blake, "Blake replaced the arid atheism or

tepid deism of the encyclopaedists and their disciples with a glowing

new personal religion" (»35).

Besides rejecting "arid atheism" and "tepid deism,"

Blake also attacked conventional religion.

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell he wrote "Prisons

are built with stones of Law, Brothels with bricks of Religion" and "As the caterpillar chooses the fairest leaves to lay her

eggs on, so the priest lays his curse on the fairest joys" ["Proverbs" 19; "Proverbs" 20]. Rather than accepting

a traditional religion from an organized church, Blake designed his

own mythology to accompany his personal, revealed religion. Blake's

personal religion was an outgrowth of his search for the Everlasting

Gospel, which he believed to be the original, pre-Jesus revelation which

Jesus preached. As Blake said, "all had originally one language

and one religion: this was the religion of Jesus, the everlasting Gospel.

Antiquity preaches the Gospel of Jesus". Blake's religion was based

upon the joy of man, which he believed glorified God. The Marriage

of Heaven and Hell culminates in the 'Song of Liberty', a hymn

of faith in revolution, ending with the affirmation that "everything

that lives is Holy" (»36).

The

book includes a famous criticism of Milton and the "Proverbs of

Hell", 70 pithy aphorisms that are notable for their praise of

heroic energy and their sense of creative vitality. In Visions of the

Daughters of Albion Blake develops the theme of sexual freedom suggested

in several of the Songs of Experience. The central figure in

the poem, Oothoon, finds that she has attained to a new purity through

sexual delight and regeneration. In this poem the repressive god of

abstract morality is first called Urizen.

|

About 1789 Blake and his

wife had moved to a small house on the south side of the Thames

in a terrace called Hercules Buildings, Lambeth. They

lived there for seven years, and this, the period of Blake's greatest

worldly prosperity, was also that of his deepest spiritual uncertainty.

Here he set about making a number of books embodying his philosophical

system, which he expressed in an increasingly obscure form. These

have become known as his Prophetic Books, their production going

on at the same time as he was painting numbers of pictures and

making large colour prints, using a tempera medium instead of

oil paints for the former. In the Prophetic

Book – America, A Prophecy (1793), Europe, A Prophecy (1794), The Book of Urizen (1794), The Book of Ahania, The

Book of Los, and The Song

of Los (all 1795) – Blake elaborates a series

of cosmic myths and epics through which he sets forth a complex

and intricate philosophical scheme. A principal symbolic figure

in these books is Urizen, a spurned and outcast immortal who embodies

both Jehovah and the forces of reason and law that Blake viewed

as restricting and suppressing the natural energies of the human

soul (»37).

|

The Prophetic Books describe a series

of epic battles fought out in the cosmos, in history, and in the human

soul, between entities symbolizing the conflicting forces of reason

(Urizen), imagination (Los), and the spirit of rebellion (Orc). America,

illustrated with brilliantly coloured designs, is a powerful short narrative

poem giving a visionary interpretation of the American Revolution as

the uprising of Orc, the spirit of rebellion. Europe shows the coming

of Christ and the French Revolution of the late 18th century as part

of the same manifestation of the spirit of rebellion. The Book of Urizen

is Blake's version of the biblical Book of Genesis. Here the Creator

is not a beneficent, righteous Jehovah, but Urizen, a "dark power"

whose rebellion against the primeval unity leads to his entrapment in

the material world. The poetry of The Book

of Urizen, written in short unrhymed lines of three accents,

has a gloomy power, but is inferior in effect to the magnificent accompanying

designs, which have an energy and monumental grandeur anticipating the

quality of those of Jerusalem, Blake's most splendid illuminated book.

Blake's saga of myths is continued in The

Book of Ahania, a kind of Exodus following the Genesis of

Urizen, and in The Book of Los.

In The Song of Los Blake returns

to the cosmic theme and brings the story of humanity down to his own

time. By this time Blake seems to have reached his spiritual nadir,

and his poetry peters out in the last of the Prophetic books. He had

lost faith in the French Revolution as an apocalyptic and regenerating

force, and was finding his attempt at a synthesis based on the "contraries"

of good and evil inadequate as an answer to the complexities of human

existence (»38).

Blake

was in many ways typical of his age and like William Morris seventy years later, he was just as typical in his fascination with

the medieval. Gothic stories and melodramas of castles, knights and

monks and fair ladies were already popular enough for Jane Austen to

parody in Northanger Abbey. Matthew Lewis's notorious soft-porn The

Monk sold very well indeed. Scott, not Wordsworth, became the favourite

poet of the age (»39).

Blake,

unfortunately for him, was captured, not by the clarity and humour of Chaucer, much as he admired him, but by the cloudy

pseudo-medievalism of Chatterton and Ossian (»40).

This kind of writing is most suitable for escapist literature, but Blake

used it for most of his work in 'illuminated printing', to convey his

most urgent messages. Apart from the Songs (1789-94), virtually all his completed books are such gothic legends.

Grandiose, superhuman figures gesticulate across his pages; and since

they crowd past, not to entertain us but to evangelise, bearing names

we have never heard of and associations we can slowly grasp, it is not

surprising that Blake's major poetry, far from bringing him fame, brought

only ridicule. When later he added to his myth the fumblings of antiquaries

– notably the theories of William Stukeley –

who identified Eastern religions with ancient Britain, linked the Syrian

mother-goddess with Avebury and the Druids with the biblical patriarchs,

even his best friends found it almost impossible to follow his imaginative

fights; and so do we (»41).

In his so-called Prophetic Books, a series of longer poems written from

1789 on, Blake created a complex personal mythology and invented his

own symbolic characters to reflect his social concerns. A true original

in thought and expression, he declares in one of these poems, “I

must create a system or be enslaved by another man's”.

With The Song of Los the experimental

period of his poetic career ended: he engraved no more books for nearly

10 years. In 1795 he had been commissioned by a bookseller to make designs

for an edition of Edward Young's Night Thoughts.

He worked on this until 1797, producing 537 watercolour drawings. It

seems to have been while he was working on these illustrations that

a fresh creative impulse led to the beginning of his first full-scale

epic poem. The first draft of the epic, called Vala, was begun in 1795. He worked on it for about nine

years, during which period he rewrote it under the title of The

Four Zoas, but never engraved it. It remains a magnificent

torso, but the quality of this work's poetry and its thought are obscured

by its overly complicated mythological scheme. In spite of the grandeur

of individual passages and of the major conception, The Four Zoas remains fragmentary and lacking in coherence. It provided the materials

out of which Blake constructed his later epics, Milton and Jerusalem (»42).

In

1800, at the invitation of William Hayley, a Sussex

squire, Blake and his wife went to live in a cottage provided by Hayley

at Felpham on the Sussex coast, where he lived and worked until 1803

under the patronage of Hayley. There he experienced profound spiritual

insights that prepared him for his mature work, the great visionary

epics written and etched between about 1804 and 1820. Milton (1804-08), Vala, or The Four Zoas (that is, aspects

of the human soul, 1797; rewritten after 1800), and Jerusalem (1804-20) have neither traditional plot, characters, rhyme, nor meter;

the rhetorical free-verse lines demand new modes of reading. They envision

a new and higher kind of innocence, the human spirit triumphant over

reason.

In

his new vision of the ideal world, all beings are united in one perfect

Human Form. After the Fall - which as always in Blake is a failure of

the imagination - the Human is fragmented, and hostility arises between

his now separated elements. None of these elements is perfectly good

or evil; the creatures of the earlier myth, Orc, Urizen and Los, are

now all damaged pieces of the Universal Human Form, and none will be

complete without the rest. From this time on, Urizen, the great evil

of America (1793), becomes less

hated and more pitied. Even Vala, the female form who is at first blamed

for the disintegration, is at last regenerated (»43).

William

Hayley, a well-meaning, obtuse dilettante, who had employed Blake to

make engravings, regarded his imaginative works with contempt and tried

to turn him into a miniature painter and tame poet on his estate. At

first Blake was delighted with life in Sussex, but he soon found the

patronizing Hayley intolerable. The cottage was damp and Mrs. Blake's

health suffered, and in 1803 the Blake returned to London. Toward the

end of his stay at Felpham, Blake was accused by a soldier called Schofield

of having uttered seditious words when he had ejected him from his cottage

garden. He was tried at the quarter sessions at Chichester, denied the

charges, and was acquitted. Hayley gave bail for Blake and employed

counsel to defend him. This experience became part of the mythology

underlying Jerusalem and Milton (»44).

It was also probably

at Felpham that Blake wrote the most notable of his later lyrical

poems, including "Auguries of Innocence", with its memorable

opening stanza:

"To

see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour."

It was at Felpham,

too, that he wrote some of his finest letters, many of them addressed

to Thomas Butts, a government clerk who was for years a generous and

loyal supporter and patron of Blake and who commissioned almost his

total output of paintings and watercolours at this period.

In

1804-08 Blake engraved Milton. This poem is a comparatively

brief epic, which deals with a contest between the hero (Milton) and

Satan; it too is couched in the prophetic grandeur and obscurity of

Blake's invented mythology. Milton's struggle with evil in the poem

is a reflection of Blake's own conflicts with the domineering patronage

of William Hayley.

Jerusalem is Blake's third major

epic and his longest poem. Begun about 1804, and written and engraved

soon after the completion of Milton, it is also the most richly decorated

of Blake's illuminated books, and only a few of its 100 plates are without

illustration. Although the details are complex and present many difficulties,

the poem's main outlines are simple. At the opening of the poem the

giant Albion (who represents both England and humanity) is shown plunged

into the "Sleep of Ulro," or the hell of abstract materialism.

The core of the poem describes his awakening and regeneration through

the agency of Los, the archetypal craftsman or creative man. The poem's

consummation is the reunion of Albion with Jerusalem (his lost soul)

and with God through his acceptance of Jesus' doctrine of universal

brotherhood (»45).

During

Blake's Felpham years another enthusiasm arrived, close on the heels

of the Immortal Man. It is a time once more for the restatement of the

vision and the third development of the myth, not this time through

disillusionment but because his images had taken a new colouring. Markedly

Christian language begins to creep into Vala, which eventually collapses

under the strain. Even before Felpham, Blake has used the phrase, "We

who call ourselves Christians". Now the belief grows into its own

images which must be incorporated into the myth.

It

is a complex development. The Druids of Ancient Britain are identified

with the patriarchs of the Bible, and the Giant Albion - the Spirit

of Britain - is identified with the Israel of the Bible. Thus Albion

is the Holy Land, London is Jerusalem, and Jesus did indeed walk (in

the truth of the imagination) across these hills. The solution to the

disintegration of man is reconciliation through forgiveness, and the

reconciliation of Christ and Albion brings about the reunion of the

disintegrated Eternal Human, who appears then as Christ himself. It

is not enough now, as in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, to

find one's own imaginative life. The Human Form Divine will not be re-created

until the whole nation, the whole of mankind, the whole universe, is

drawn together; but this can begin in the smallest of single actions.

Blake has returned to the idealistic hope of America, but now his thought

is less simple and more mystical; yet as the pages of Jerusalem show,

no less radical (»46).

Blake's

life during the period from 1803 to about 1820 was one of worldly failure.

He found it difficult to get work, and the engravings that can be identified

as his from this period are often hack jobs. In 1809 he made a last

effort to put his work before the public and held an exhibition of 16

paintings and watercolour drawings. He wrote a thoughtful Descriptive

Catalogue for the exhibition, but only a few people attended. But

after this long period of obscurity, Blake found in 1819 a new and generous

patron in the painter John Linnell, who introduced

him to a group of young artists among whom was Samuel Palmer. In his

last years Blake became the centre of this group, whose members shared

Blake's religious seriousness and revered him as their master.

The

most notable poetry Blake wrote after Jerusalem is to be found

in The Everlasting Gospel (1818?),

a fragmentary and unfinished work containing a challenging reinterpretation

of the character and teaching of Christ. Blake's writings also include An Island in the Moon (1784), a rollicking satire on events

in his early life; a collection of letters; and a notebook containing

sketches and some shorter poems dating between 1793 and 1818. It was

called the Rossetti Manuscript,

because it was acquired in 1847 by the English poet Dante Gabriel

Rossetti, one of the first to recognize Blake's genius.

But

Blake's last years were devoted mainly to pictorial art. In 1821 Linnell

commissioned him to make a series of 22 watercolours inspired by the

Book of Job; these include some of his best known pictures. Linnell

also commissioned Blake's designs for Dante's Divine

Comedy, begun in 1825 and left unfinished at his death. These consist

of 102 watercolours notable for their brilliant colour. Blake thus found

in his 60s a following and support for the imaginative work he had longed

to do all his life. As a result, it was in his last years that he produced

his most technically assured and beautiful designs. Toward the end of

his life Blake still coloured copies of his books while resting in bed,

and that is how he died in a room off the Strand, in London, on the

12th August 1827, – in his 70th year – leaving uncompleted

a cycle of drawings inspired by Dante's Divine Comedy. He was

buried in an unmarked grave in Bunhill Fields.

Blake

is frequently referred to as a mystic, but this is not really accurate.

He deliberately wrote in the style of the Hebrew prophets and apocalyptic

writers. He envisioned his works as expressions of prophecy, following

in the footsteps (or, more precisely strapping on the sandals) of Elijah

and Milton. In his filthy London studio he succumbed to constant visions

of angels and prophets who instructed him in his work. He once painted

while receiving a vision of Voltaire, and when asked later whether Voltaire

spoke English, replied: "To my sensations it was English. It was

like the touch of a musical key. He touched it probably French, but

to my ear it became English." (»47)

It

is the difficulty of Blake's visionary poetry, rather than the vividness

that has captured the commentators. They have sought high and low in

the mystical philosophies, or in the politics, of East and West for

the "key" to his work. It is true that he has a habit of allusiveness

that is certainly obscure. In the famous song, for example, England

is 'clouded' by spiritual blindness more than by cumuli, and the 'Satanic

mills' are the shackles of the mind, of which the Industrial Revolution

is only one manifestation. The difficulty is not to be solved by finding

a missing key. It is something less systematic; the problem of Blake

himself.

Each

of Blake's new enthusiasm reshapes the legend of his poems. As Blake

refines his beliefs, he refines his myth too. The function of Orc and

Urizen in America (1793) is quite plain; one fights for freedom,

the other for law. In The Book of Urizen (1794) it is much

more complex, and by Vala (1803) and Milton (1810)

they have had to be altered almost out of recognition, but they are

never quite abandoned. Blake was not by instinct a narrative poet. He

tended to 'improve' his longer poems by a process of accumulation rather

than by following the demands of the narrative. His mind was like an

untidy desk. He threw nothing away, and often used old material for

new tasks. One never knows what one will find. The reader ploughing

through pages full of 'dismal howling woe' comes across an unexpected

line of startling beauty which only Blake could have written (»48).

It

is therefore no use trying to understand Blake by means of a key. No

one scheme fits all his works; each stage grows out of the one preceding

it. Each enthusiasm gives a striking new turn to his legend and its

imagery, but the new is always superimposed on the old. If we can understand

the series of enthusiasms, we can begin to find our way through the

difficulties of his work.

It is easy to dismiss Blake as 'primitive', an artist whose attraction

resides in his naivety, which is lost when the work becomes heavy and

charmless. This is also too simple. There is an odd contradiction at

the heart of Blake's writing. He repeatedly called for art to concern

itself with the 'minute particulars' of life: "To generalise is

to be an idiot!" he scribbled in the margin of Reynold's Discourses (»49).

On the other hand he criticized Wordsworth for paying too much attention

to the details of nature at the expense of inner realities (»50).

More important, much of his poetry disregards his own rule. Words like

'howling' and 'dismal' appear far too often. His lyrics are usually

marvels of conciseness, but he chose to express his dearest beliefs,

not as 'minute particulars', but as cloudy, generalized figures representing

eternal states of humanity. Milton ceases to be a seventeenth-century

poet and becomes a state of Los, the eternal spirit of the imagination.

From first to last, Blake champions the imagination, but too much misplaced

convention. At his greatest, minutiae become eternal; at his worst,

the eternal becomes a scheme (»51).

Here

if anywhere else, lies the "key" to Blake. He was not a "Romantic"

writer, whatever that is; he was neo-classic by training and inclination.

He had no time for classical myth, but that is irrelevant. His instinct

was to create – inspired by his own visions – not symbols

out of mystical tradition, nor vivid observations of human life, but

representative figures to embody both the inner nature of the subject

and his own response to it. His long epic poems are made up of a mixture

of inspiration, pig-headedness, evangelic fervour and profound imagery.

When he failed, he became obscure or tedious – often both. When

he succeeded, he created a kind of magic of which no other poet has

been capable. He blundered into greatness, just as he often blundered

away from it. Yet there are many occasions, as his mystical figures

move across the abyss, when all the elements come together, and then

he produces poetry of a unique kind of genius, which leave the reader

in something more than admiration – in wonderment.

Footnotes:

(1) Appelbaum, Stanley - Introduction to English Romantic Poetry: An Anthology. [Mineola, Dover, 1996.] (Chpt. V.)

(2) Damon, S. Foster - A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. [New York, Dutton, 1971.] (Chpt. IX.)

(3) Murry, John Middleton - William Blake. [London, Jonathan Cape, 1933.] (p.12.)

(4) Mack, Maynard (ed.) - "William Blake" in The Norton Anthology: World Masterpieces, Expanded Edition, Volume 2. [New York: Norton, 1995.] (p. 783.)

(5) Frye, Northrop - Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake. [Boston, Beacon Press, 1967.] (Chpt. 8.)

(6) c.a. (Chpt. 4.)

(7) Appelbaum, Stanley - Introduction to English Romantic Poetry: An Anthology. [Mineola, Dover, 1996.] (Chpt.

V.)

(8) Keynes, Geoffrey - William Blake: Songs of Innocence and of Experience. [New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.] ("An Introduction to William Blake")

(9) Wilson, Mona - The Life of William Blake. [(ed.) Geoffrey Keynes. London, Oxford University Press, 1971.]

(10) Wilson, Mona - The Life of William Blake. [(ed.) Geoffrey Keynes. London, Oxford University Press, 1971.]

(11) Bindman, David - Blake as an Artist. [Oxford, Phaidon, 1977.] (p. 53-56.)

(12) Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.]

(13) Bindman, David - William Blake, His Art and Times. [Thames and Hudson, 1982.] (p. 15-23.)

(14) c.a. (p. 45.)

(15) Blunt, Anthony - The Art of William Blake. [Columbia University Press, New York, 1963.] (p. 78.)

(16) Keynes, Geoffrey - William Blake: Songs of Innocence and of Experience. [New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.] ("An Introduction to William Blake")

(17) Blunt, Anthony - The Art of William Blake. [Columbia University Press, New York, 1963.] (p. 12.)

c.a. (p. 34.)

(18) Keynes, Geoffrey - William Blake: Songs of Innocence and of Experience. [New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.] ("An Introduction to William Blake")

(19) Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.]

(20) Keynes, Geoffrey - William Blake: Songs of Innocence and of Experience. [New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.] ("An Introduction to William Blake")

(21) Bindman, David - Blake as an Artist. [Oxford, Phaidon, 1977.] (p.58.)

(22) Mitchell, W.J.T. - Blake's Composite Art: A Study of the Illuminated Poetry. [Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1978.] (p. 13.)

(23) Bindman, David - William Blake, His Art and Times. [Thames and Hudson, 1982.] (p. 45-50.)

(24) Appelbaum, Stanley - Introduction to English Romantic Poetry: An Anthology. [Mineola, Dover, 1996.] (Chpt. V.)

(25) Damon, S. Foster - A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. [New York, Dutton, 1971.] (p. 318.)

(26) Mack, Maynard (ed.) - "William Blake" in The Norton Anthology: World Masterpieces, Expanded Edition, Volume 2. [New York: Norton, 1995.] (p.784.)

(27) Mack, Maynard (ed.) - "William Blake" in The Norton Anthology: World Masterpieces, Expanded Edition, Volume 2. [New York: Norton, 1995.] (p.785.)

(28) Varanyi Szilvia - Sin and Error in William Blake. [Budapest, ELTE-BTK DELL, Szakdolgozat 19xx.]

(29) Erdman, David V. – Blake: Prophet against Empire. [Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.] (p. 45.)

(30) Nurmi, Martin K. - William Blake. [London, Hutchinson, 1975.] (p. 54.)

(31) Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.] (p. 79.)

(32) c.a. (p. 124.)

(33) Damon, S. Foster - A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. [New York, Dutton, 1971.] (Chpt. XI.)

(34) Appelbaum, Stanley - Introduction to English Romantic Poetry: An Anthology. [Mineola, Dover, 1996.] (Chpt. III.)

(35) Damon, S. Foster - A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. [New York, Dutton, 1971.] (p. 344.)

(36) Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.]

(37) Damon, S. Foster - A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. [New York, Dutton, 1971.]

(38) Appelbaum, Stanley - Introduction to English Romantic Poetry: An Anthology. [Mineola, Dover, 1996.] (Chpt. I.)

(39) Phillips, Michael (ed.) - Interpreting Blake. [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.] (p. 193.)

(40) Fisher, F. Peter - Blake and the Druids. [in Frye (ed.): Blake . Prentice-Hall, New Jersey 1966.]

(41) Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.]

(42) Damon, S. Foster - William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols. [Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1958.]

(43) Wilson, Mona - The Life of William Blake. [(ed.) Geoffrey Keynes. London, Oxford University Press, 1971.]

(44) Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.]

(45) Nathan, Norman - Prince William B. - The Philosophical Conceptions of William Blake. [Paris, Mouton, 1975.]

(46) Levi Asher - Literary Kicks on William Blake.

(47) Phillips, Michael (ed.) - Interpreting Blake. [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.] (p. 114-116.)

(49) Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.] (p. 106.)

(50) c.a. (p.112.)

(51) Behrendt, Stephen C. - Reading William Blake. [London, Macmillan Press, 1992.] (p. 87.)

|